With the 2016 winner’s announcement imminent, we caught up with brilliant author Hanya Yanagihara to discuss the inspiration behind her hugely popular shortlisted novel A Little Life.

I have spoken before of how this book was born from other people’s artwork: specifically, a few dozen paintings, drawings, and photographs I’d kept (as printouts or on my computer) for years. I of course knew I was drawn to these images, but it wasn’t until I began imagining what this book might be that I realized that I had, in fact, been collecting the stuff of my novel itself. Here it was: in these images were the themes, the tones, the questions and emotions that I wanted to convey not in light or color, but in words. These are some of the pictures I turned to again and again as I wrote A Little Life.

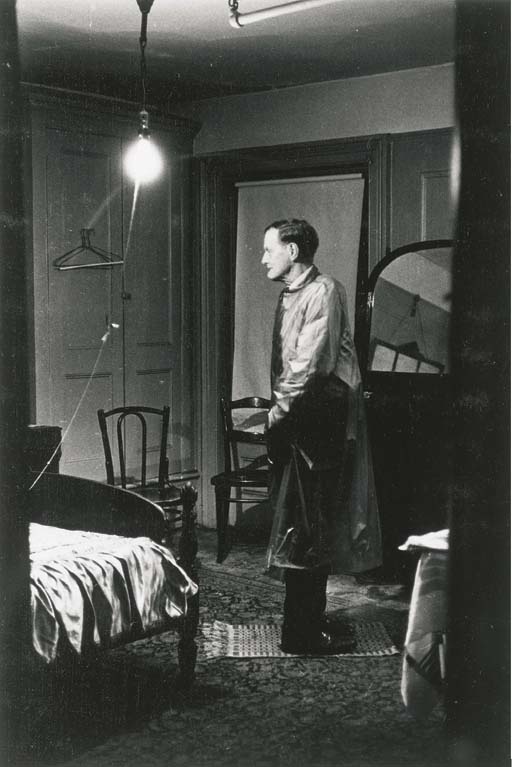

“The Backwards Man in His Hotel Room,” by Diane Arbus (1961)

This image isn’t one of the photographer’s strongest: it’s a little grainy and has a furtive, voyeuristic quality that her later work doesn’t. But when I saw it, probably in 2004, I was struck by how completely, almost unbearably, it conveyed the state and feeling of loneliness. And not just loneliness, but the sense of being, literally, at odds with your own body. The man here is probably a contortionist–his feet point one way, his head another–but when I initially encountered it, I for a minute thought he’d simply put on all his clothes backwards, that he was performing only for himself in this small and ugly room. The apparent truth of it doesn’t change how I felt (and feel) about it, though. I do remember that at the time, I had though, “I’m going to write a story to accompany this photo.” And so I did.

“Untitled 5/59,” by Bill Henson (1990-91)

The truest portrait is the one that’s made of us without us knowing: certainly that’s the case with Henson’s “Paris Opera Project,” for which the artist took photographs of opera-goers rapt with attention. These chiaroscuro images are not only beautiful, but capture with great accuracy our vulnerability when we surrender to art, when we can do nothing but look and listen. I make direct reference to this picture in Part I of the book, when JB takes a photograph of Jude at a play just at the moment he smiles.

“Untitled No. 3878,” by Todd Hido (1968)

I’ve spoken and written before about the particular Americanness of the roadside motel: a physical space that feels as emblematic as the mall, the highway, and the drive-through. Its entire nature is transitional — to stay in one is to be reminded of the vastness, and of the brevity, of life itself. As I’ve also written, there are so many great American photographers who’ve taken great photos of motels: Joel Sternfeld, Alec Soth, P.L. diCorcia, Stephen Shore, and on and on. But one of the specific images I kept in mind is this one, from Todd Hido’s “Interiors” series, for which the artist took photographs of abandoned spaces–foreclosed houses and motels–that have in common a sort of compelling unlovedness. Although they may be structures that do in fact offer protection from the weather, there’s also something so intensely lonely and spiritless about them that they appear unliveable. I pictured Jude spending his time in a bed very much like this one, with Brother Luke just on the other side of the wall.

To find out more about A Little Life and see the 2016 shortlist in full click here. Don’t forget to tell us what you think of the books on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.